Eastern Brown Snake on:

[Wikipedia]

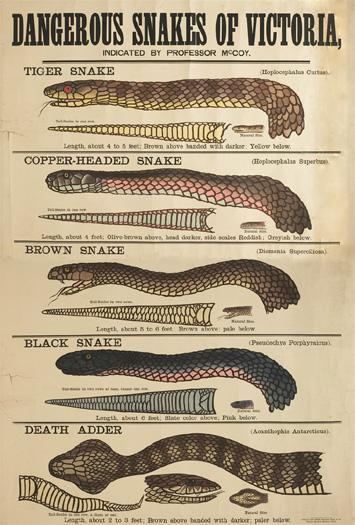

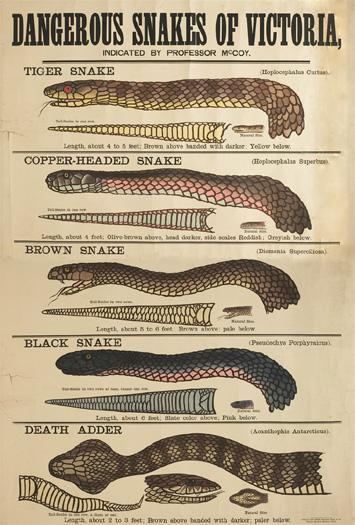

[Google]

[Amazon]

The eastern brown snake (''Pseudonaja textilis''), often referred to as the common brown snake, is a

The eastern brown snake is of slender to average build with no demarcation between its head and neck. Its snout appears rounded when viewed from above. Most specimens have a total length (including tail) up to , with some large individuals reaching . The maximum recorded total length for the species is . Evidence indicates that snakes from the northern populations tend to be larger than those from southern populations. The adult eastern brown snake is variable in colour. Its upper parts range from pale to dark brown, or sometimes shades of orange or russet, with the pigment more richly coloured in the posterior part of the dorsal scales. Eastern brown snakes from Merauke have tan to olive upper parts, while those from eastern Papua New Guinea are very dark grey-brown to blackish.

The eastern brown snake's fangs are small compared to those of other Australian venomous snakes, averaging in length or up to in larger specimens, and are apart. The tongue is dark. The

The eastern brown snake is of slender to average build with no demarcation between its head and neck. Its snout appears rounded when viewed from above. Most specimens have a total length (including tail) up to , with some large individuals reaching . The maximum recorded total length for the species is . Evidence indicates that snakes from the northern populations tend to be larger than those from southern populations. The adult eastern brown snake is variable in colour. Its upper parts range from pale to dark brown, or sometimes shades of orange or russet, with the pigment more richly coloured in the posterior part of the dorsal scales. Eastern brown snakes from Merauke have tan to olive upper parts, while those from eastern Papua New Guinea are very dark grey-brown to blackish.

The eastern brown snake's fangs are small compared to those of other Australian venomous snakes, averaging in length or up to in larger specimens, and are apart. The tongue is dark. The

The eastern brown snake is generally solitary, with females and younger males avoiding adult males. It is active during the day, though it may retire in the heat of hot days to come out again in the late afternoon. It is most active in spring, the males venturing out earlier in the season than females, and is sometimes active on warm winter days. Individuals have been recorded basking on days with temperatures as low as . Occasional nocturnal activity has been reported. At night, it retires to a crack in the soil or burrow that has been used by a house mouse, or (less commonly) skink, rat, or rabbit. Snakes may use the refuge for a few days before moving on, and may remain above ground during hot summer nights. During winter, they hibernate, emerging on warm days to sunbathe. Fieldwork in the

The eastern brown snake is generally solitary, with females and younger males avoiding adult males. It is active during the day, though it may retire in the heat of hot days to come out again in the late afternoon. It is most active in spring, the males venturing out earlier in the season than females, and is sometimes active on warm winter days. Individuals have been recorded basking on days with temperatures as low as . Occasional nocturnal activity has been reported. At night, it retires to a crack in the soil or burrow that has been used by a house mouse, or (less commonly) skink, rat, or rabbit. Snakes may use the refuge for a few days before moving on, and may remain above ground during hot summer nights. During winter, they hibernate, emerging on warm days to sunbathe. Fieldwork in the

Clinically, the venom of the eastern brown snake causes venom-induced consumption coagulopathy; a third of cases develop serious systemic envenoming including

Clinically, the venom of the eastern brown snake causes venom-induced consumption coagulopathy; a third of cases develop serious systemic envenoming including

Video: Eastern or Common Brown Snake

{{featured article Pseudonaja Reptiles of Papua New Guinea Reptiles of Western Australia Reptiles of Western New Guinea Reptiles described in 1854 Taxa named by André Marie Constant Duméril Taxa named by Gabriel Bibron Taxa named by Auguste Duméril Snakes of Australia Reptiles of New South Wales Reptiles of Queensland Snakes of New Guinea Reptiles of Victoria (Australia)

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of highly venomous snake

Venomous snakes are Species (biology), species of the Suborder (biology), suborder Snake, Serpentes that are capable of producing Snake venom, venom, which they use for killing prey, for defense, and to assist with digestion of their prey. The v ...

in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Elapidae

Elapidae (, commonly known as elapids ; grc, ἔλλοψ ''éllops'' "sea-fish") is a family of snakes characterized by their permanently erect fangs at the front of the mouth. Most elapids are venomous, with the exception of the genus Emydoceph ...

. The species is native to eastern and central Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and southern New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. It was first described by André Marie Constant Duméril

André Marie Constant Duméril (1 January 1774 – 14 August 1860) was a French zoologist. He was professor of anatomy at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle from 1801 to 1812, when he became professor of herpetology and ichthyology. His ...

, Gabriel Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was hir ...

, and Auguste Duméril

Auguste Henri André Duméril (30 November 1812 – 12 November 1870) was a French zoologist. His father, André Marie Constant Duméril (1774-1860), was also a zoologist. In 1869 he was elected as a member of the Académie des sciences.

Duméril ...

in 1854. The adult eastern brown snake has a slender build and can grow to in length. The colour of its surface ranges from pale brown to black, while its underside is pale cream-yellow, often with orange or grey splotches. The eastern brown snake is found in most habitats except dense forests, often in farmland and on the outskirts of urban areas, as such places are populated by its main prey, the house mouse

The house mouse (''Mus musculus'') is a small mammal of the order Rodentia, characteristically having a pointed snout, large rounded ears, and a long and almost hairless tail. It is one of the most abundant species of the genus '' Mus''. Althoug ...

. The species is oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and ...

. The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

classifies the snake as a least-concern species

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

, though its status in New Guinea is unclear.

Considered the world's second-most venomous land snake after the inland taipan (''Oxyuranus microlepidotus''), based on its value ( subcutaneous) in mice

A mouse ( : mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

, it is responsible for about 60% of human snake-bite deaths in Australia. The main effects of its venom are on the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

—coagulopathy

Coagulopathy (also called a bleeding disorder) is a condition in which the blood's ability to coagulate (form clots) is impaired. This condition can cause a tendency toward prolonged or excessive bleeding (bleeding diathesis), which may occur spo ...

, haemorrhage (bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

), cardiovascular collapse

Shock is the state of insufficient blood flow to the tissues of the body as a result of problems with the circulatory system. Initial symptoms of shock may include weakness, fast heart rate, fast breathing, sweating, anxiety, and increased thi ...

, and cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. It is a medical emergency that, without immediate medical intervention, will result in sudden cardiac death within minutes. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and possib ...

. One of the main components of the venom is the prothrombinase The prothrombinase complex consists of the serine protease, Factor Xa, and the protein cofactor, Factor Va. The complex assembles on negatively charged phospholipid membranes in the presence of calcium ions. The prothrombinase complex catalyzes the ...

complex pseutarin-C, which breaks down prothrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma- ...

.

Taxonomy

John White, the surgeon-general of theFirst Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

to New South Wales, wrote, ''A Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales'' in 1790, which described many Australian animal species for the first time. In it, he reported a snake that fits the description of the eastern brown snake, but did not name it. French zoologists André Marie Constant Duméril

André Marie Constant Duméril (1 January 1774 – 14 August 1860) was a French zoologist. He was professor of anatomy at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle from 1801 to 1812, when he became professor of herpetology and ichthyology. His ...

, Gabriel Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was hir ...

, and Auguste Duméril

Auguste Henri André Duméril (30 November 1812 – 12 November 1870) was a French zoologist. His father, André Marie Constant Duméril (1774-1860), was also a zoologist. In 1869 he was elected as a member of the Académie des sciences.

Duméril ...

were the first to describe

Shneur Hasofer is a Hasidic musician known as DeScribe. Hasofer's musical style has been characterized as "Hasidic hip-hop," "Hasidic rap" and "Hasidic R&B".

Background

Hasofer was born to a Chabad Hasidic family in Melbourne, Australia. Hasof ...

the species in 1854. They gave it the binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''Furina textilis'' – (knitted furin) in French – from a specimen collected in October 1846 by Jules Verreaux

Jules Pierre Verreaux (24 August 1807 – 7 September 1873) was a French botanist and ornithologist and a professional collector of and trader in natural history specimens. He was the brother of Édouard Verreaux and nephew of Pierre Antoine Dela ...

, remarking that the fine-meshed pattern on the snake's body reminded him of fine stockings, which was the inspiration for the name. Due to differences in appearance, different specimens of the eastern brown snake were categorised as different species in the early 19th century. German herpetologist Johann Gustav Fischer

Johann Gustav Fischer (1 March 1819, Hamburg – 27 January 1889) was a German herpetologist.

He served as an instructor at the Johanneum in Hamburg, and was associated with the city's ''Naturhistorisches Museum'', working extensively with its h ...

described it as ''Pseudoelaps superciliosus'' in 1856, from a specimen collected from Sydney. German-British zoologist Albert Günther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf Günther FRS, also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther (3 October 1830 – 1 February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Günther is ranked the second-most productive re ...

described the species as ''Demansia annulata'' in 1858. Italian naturalist Giorgio Jan

''Tantilla'' is a large genus of harmless New World snakes in the family Colubridae. The genus includes 66 species, which are commonly known as centipede snakes, blackhead snakes, and flathead snakes.Wilson, Larry David. 1982. Tantilla. ...

named ''Pseudoelaps sordellii'' and ''Pseudoelaps kubingii'' in 1859.

Gerard Krefft

Johann Ludwig (Louis) Gerard Krefft (17 February 1830 – 19 February 1881), a talented artist and draughtsman, and the Curator of the Australian Museum for 13 years (1861-1874), was one of Australia's first and most influential zoologists and ...

, curator of the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

, reclassified Duméril, Bibron, and Duméril's species in the genus ''Pseudonaia'' icin 1862 after collecting multiple specimens and establishing that the markings of young snakes faded as they grew into adult brown snakes. He concluded the original description was based on an immature specimen and sent an adult to Günther, who catalogued it under the new name the same year when cataloguing new species of snakes in the British Museum's collection. After examining all specimens, Günther concluded that ''Furina textilis'' and ''Diemansia annulata'' were named for young specimens and ''Pseudoelaps superciliosus'', ''P. sordelli'', and ''P. kubingii'' were named for adults, and all represented the same species, which he called ''Diemenia superciliosa''. Belgian-British naturalist George Albert Boulenger

George Albert Boulenger (19 October 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a Belgian-British zoologist who described and gave scientific names to over 2,000 new animal species, chiefly fish, reptiles, and amphibians. Boulenger was also an active botani ...

called it ''Diemenia textilis'' in 1896, acknowledging Duméril, Bibron, and Duméril's name as having priority. In subsequent literature, it was known as ''Demansia textilis'' as ''Diemenia'' was regarded as an alternate spelling of ''Demansia''.

The brown snakes were moved from ''Diemenia/Demansia'' to ''Pseudonaja'' by Australian naturalist Eric Worrell

Eric Arthur Frederic Worrell (MBE), (27 October 1924 – 13 July 1987) was an Australian naturalist, herpetologist and writer whose collection of snake venom was essential in the production of snake anti-venom in Australia.

History

Eric was b ...

in 1961 on the basis of skull morphology, and upheld by American herpetologist Samuel Booker McDowell in 1967 on the basis of the muscles of the venom glands. This classification has been followed by subsequent authors. In 2002, Australian herpetologist Richard W. Wells split the genus ''Pseudonaja'', placing the eastern brown snake in the new genus ''Euprepiosoma'', though this has not been recognised by other authors, and Wells has been strongly criticised for a lack of rigour in his research.

Within the genus ''Pseudonaja'', the eastern brown snake has the largest diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

number of chromosomes at 38; those of the other species range from 30 to 36. A 2008 study of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

across its range showed three broad lineages - a southeastern clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

from South Australia, Victoria, and southeastern and coastal New South Wales; a northeastern clade from northern and western New South Wales and Queensland; and a central (and presumably northern) Australian clade from the Northern Territory. The central Australian clade had colonised the region around Merauke

Merauke is a large town and the capital of the South Papua province, Indonesia. It is also the administrative centre of Merauke Regency in South Papua. It is considered the easternmost city in Indonesia. The town was originally called Ermasoe. It ...

in southern West Papua, and the northeastern clade had colonised Milne Bay

Milne Bay is a large bay in Milne Bay Province, south-eastern Papua New Guinea. More than long and over wide, Milne Bay is a sheltered deep-water harbor accessible via Ward Hunt Strait. It is surrounded by the heavily wooded Stirling Range to t ...

, Oro

Oro or ORO, meaning gold in Spanish and Italian, may refer to:

Music and dance

* Oro (dance), a Balkan circle dance

* Oro (eagle dance), an eagle dance from Montenegro and Herzegovina

* "Oro" (song), the Serbian entry in the 2008 Eurovision S ...

, and Central Provinces

The Central Provinces was a province of British India. It comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Its capital was Nagpur. ...

in eastern Papua New Guinea in the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

via landbridges between Australia and New Guinea.

''P. textilis'' is monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispec ...

. Raymond Hoser

Raymond Terrence Hoser (born 1962) is an Australian snake-catcher and author. Since 1976, he has written books and articles about official corruption in Australia. He has also written works on Australian frogs and reptiles. Hoser's work on herp ...

described all New Guinea populations as ''Ps. t. pughi'' based on a differing maxillary tooth count from Australian populations; this difference was inconsistent, and as no single New Guinea population is genetically distinct, the taxon is not recognised. Wells and C. Ross Wellington described ''Pseudonaja ohnoi'' in 1985 from a large specimen from Mount Gillen near Alice Springs

Alice Springs ( aer, Mparntwe) is the third-largest town in the Northern Territory of Australia. Known as Stuart until 31 August 1933, the name Alice Springs was given by surveyor William Whitfield Mills after Alice, Lady Todd (''née'' Al ...

, distinguishing it on the basis of scale numbers, but it is not regarded as distinct.

The species is commonly called the eastern brown snake or common brown snake. It was known as to the Eora

The Eora (''Yura'') are an Aboriginal Australian people of New South Wales. Eora is the name given by the earliest European settlers to a group of Aboriginal people belonging to the clans along the coastal area of what is now known as the Sy ...

and Darug

The Dharug or Darug people, formerly known as the Broken Bay tribe, are an Aboriginal Australian people, who share strong ties of kinship and, in pre-colonial times, lived as skilled hunters in family groups or clans, scattered throughout much ...

inhabitants of the Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

basin. To the Dharawal

The Dharawal people, also spelt Tharawal and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people, identified by the Dharawal language. Traditionally, they lived as hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans with ties of kinship, s ...

of the Illawarra

The Illawarra is a coastal region in the Australian state of New South Wales, nestled between the mountains and the sea. It is situated immediately south of Sydney and north of the South Coast region. It encompasses the two cities of Wollongo ...

, it is . The Dharawal and Awabakal

The Awabakal people , are those Aboriginal Australians who identify with or are descended from the Awabakal tribe and its clans, Indigenous to the coastal area of what is now known as the Hunter Region of New South Wales. Their traditional te ...

held ceremonies for the eastern brown snake. is the reconstructed name in the Wiradjuri language

Wiradjuri (; many other spellings, see Wiradjuri) is a Pama–Nyungan language of the Wiradhuric subgroup. It is the traditional language of the Wiradjuri people of Australia. A progressive revival is underway, with the language being taught ...

of southern New South Wales.

Description

The eastern brown snake is of slender to average build with no demarcation between its head and neck. Its snout appears rounded when viewed from above. Most specimens have a total length (including tail) up to , with some large individuals reaching . The maximum recorded total length for the species is . Evidence indicates that snakes from the northern populations tend to be larger than those from southern populations. The adult eastern brown snake is variable in colour. Its upper parts range from pale to dark brown, or sometimes shades of orange or russet, with the pigment more richly coloured in the posterior part of the dorsal scales. Eastern brown snakes from Merauke have tan to olive upper parts, while those from eastern Papua New Guinea are very dark grey-brown to blackish.

The eastern brown snake's fangs are small compared to those of other Australian venomous snakes, averaging in length or up to in larger specimens, and are apart. The tongue is dark. The

The eastern brown snake is of slender to average build with no demarcation between its head and neck. Its snout appears rounded when viewed from above. Most specimens have a total length (including tail) up to , with some large individuals reaching . The maximum recorded total length for the species is . Evidence indicates that snakes from the northern populations tend to be larger than those from southern populations. The adult eastern brown snake is variable in colour. Its upper parts range from pale to dark brown, or sometimes shades of orange or russet, with the pigment more richly coloured in the posterior part of the dorsal scales. Eastern brown snakes from Merauke have tan to olive upper parts, while those from eastern Papua New Guinea are very dark grey-brown to blackish.

The eastern brown snake's fangs are small compared to those of other Australian venomous snakes, averaging in length or up to in larger specimens, and are apart. The tongue is dark. The iris

Iris most often refers to:

*Iris (anatomy), part of the eye

*Iris (mythology), a Greek goddess

* ''Iris'' (plant), a genus of flowering plants

* Iris (color), an ambiguous color term

Iris or IRIS may also refer to:

Arts and media

Fictional ent ...

is blackish with a paler yellow-brown or orange ring around the pupil. The snake's chin and under parts are cream or pale yellow, sometimes fading to brown or grey-brown towards the tail. Often, orange, brown, or dark grey blotches occur on the under parts, more prominent anteriorly. The ventral scales are often edged with dark brown on their posterior edges.

Juveniles can vary in markings, but generally have a black head, with a lighter brown snout and band behind, and a black nuchal

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , "spinal marrow"). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''n ...

band. Their bodies can be uniform brown, or have many black bands, or a reticulated pattern, with all darker markings fading with age. Snake clutches in colder areas tend have a higher proportion of young snakes with banded markings on their bodies.

Its yellowish under parts serve to distinguish it from the dugite

The dugite (; ''Pseudonaja affinis'') is a species of venomous, potentially lethal, snake native to Western Australia, a member of the Family (biology), family Elapidae.

The word dugite is an anglicisation of names for the snake in some dialects ...

(''Pseudonaja affinis'') and peninsula brown snake (''P. inframacula''), which are entirely brown or brown with grey under parts. The eastern brown snake has flesh-pink skin inside its mouth, whereas the northern brown snake and western brown snake have black skin. Large eastern brown snakes are often confused with mulga snake

The king brown snake (''Pseudechis australis'') is a species of highly venomous snake of the family Elapidae, native to northern, western, and Central Australia. Despite its common name, it is a member of the genus ''Pseudechis'' (black snakes) ...

s (''Pseudechis australis''), whose habitat they share in many areas, but may be distinguished by their smaller heads. Juvenile eastern brown snakes have head markings similar to red-naped snake

The red-naped snake (''Furina diadema'') is a small venomous reptile from the family Elapidae. The snakes are found in four Australian states and are listed as 'threatened' in Victoria'.

They are nocturnal and feed on small skinks. The young ea ...

s (''Furina diadema''), grey snakes (''Hemiaspis damelii)'', Dwyer's snakes (''Suta dwyeri)'', and the curl snake (''Suta suta'').

Scalation

The number and arrangement of scales on a snake's body are a key element of identification to species level. The eastern brown snake has 17 rows ofdorsal scales

In snakes, the dorsal scales are the longitudinal series of plates that encircle the body, but do not include the ventral scales. Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004). ''The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere''. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publis ...

at midbody, 192 to 231 ventral scales, 45 to 75 divided subcaudal scales (occasionally some of the anterior ones are undivided), and a divided anal scale

Anal may refer to:

Related to the anus

*Related to the anus of animals:

** Anal fin, in fish anatomy

** Anal vein, in insect anatomy

** Anal scale, in reptile anatomy

*Related to the human anus:

** Anal sex, a type of sexual activity involv ...

. Its mouth is bordered by six supralabial scales above, and seven (rarely eight) sublabial scales below. Its nasal scale is almost always undivided, and rarely partly divided. Each eye is bordered posteriorly by two or rarely three postocular scales.

Distribution and habitat

The eastern brown snake is found along the east coast of Australia, from Malanda in far north Queensland, along the coasts and inland ranges of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and to theYorke Peninsula

The Yorke Peninsula is a peninsula located northwest and west of Adelaide in South Australia, between Spencer Gulf on the west and Gulf St Vincent on the east. The peninsula is separated from Kangaroo Island to the south by Investigator Strai ...

in South Australia. Disjunct populations occur on the Barkly Tableland and the MacDonnell Ranges

The MacDonnell Ranges, or Tjoritja in Arrernte, is a mountain range located in southern Northern Territory. MacDonnell Ranges is also the name given to an interim Australian bioregion broadly encompassing the mountain range, with an area of .< ...

in the Northern Territory. and the far east of the Kimberley in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

, and discontinuously in parts of New Guinea, specifically northern Milne Bay Province and Central Province in Papua New Guinea, and the Merauke region of Papua Province

Papua is a province of Indonesia, comprising the northern coast of Western New Guinea together with island groups in Cenderawasih Bay to the west. It roughly follows the borders of Papuan customary region of Tabi Saireri. It is bordered by the ...

, in the Indonesian part of New Guinea. It is common in southeastern Queensland between Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

and Beenleigh

Beenleigh is a town and suburb in the City of Logan, Queensland, Australia. In the , the suburb of Beenleigh had a population of 8,252 people.

A government survey for the new town was conducted in 1866. The town is the terminus for the Beenl ...

.

The eastern brown snake occupies a varied range of habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s from dry sclerophyll

Sclerophyll is a type of vegetation that is adapted to long periods of dryness and heat. The plants feature hard leaf, leaves, short Internode (botany), internodes (the distance between leaves along the stem) and leaf orientation which is paral ...

forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s (eucalypt

Eucalypt is a descriptive name for woody plants with capsule fruiting bodies belonging to seven closely related genera (of the tribe Eucalypteae) found across Australasia:

''Eucalyptus'', '' Corymbia'', '' Angophora'', ''Stockwellia'', ''Allosyn ...

forests) and heaths

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

of coastal ranges, through to savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

woodlands, inner grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur natur ...

s, and arid scrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominance (ecology), dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, Herbaceous plant, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or ...

s and farmland, as well as drier areas that are intermittently flooded. It is more common in open habitat and also farmland and the outskirts of urban areas. It is not found in alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

regions. Because of its mainly rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

diet, it can often be found near houses and farms. Such areas also provide shelter in the form of rubbish and other cover; the snake can use sheets of corrugated iron or buildings as hiding spots, as well as large rocks, burrows, and cracks in the ground.

Behaviour

The eastern brown snake is generally solitary, with females and younger males avoiding adult males. It is active during the day, though it may retire in the heat of hot days to come out again in the late afternoon. It is most active in spring, the males venturing out earlier in the season than females, and is sometimes active on warm winter days. Individuals have been recorded basking on days with temperatures as low as . Occasional nocturnal activity has been reported. At night, it retires to a crack in the soil or burrow that has been used by a house mouse, or (less commonly) skink, rat, or rabbit. Snakes may use the refuge for a few days before moving on, and may remain above ground during hot summer nights. During winter, they hibernate, emerging on warm days to sunbathe. Fieldwork in the

The eastern brown snake is generally solitary, with females and younger males avoiding adult males. It is active during the day, though it may retire in the heat of hot days to come out again in the late afternoon. It is most active in spring, the males venturing out earlier in the season than females, and is sometimes active on warm winter days. Individuals have been recorded basking on days with temperatures as low as . Occasional nocturnal activity has been reported. At night, it retires to a crack in the soil or burrow that has been used by a house mouse, or (less commonly) skink, rat, or rabbit. Snakes may use the refuge for a few days before moving on, and may remain above ground during hot summer nights. During winter, they hibernate, emerging on warm days to sunbathe. Fieldwork in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area

The Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area (MIA) is geographically located within the Riverina area of New South Wales. It was created to control and divert the flow of local river and creek systems for the purpose of food production. The main river s ...

found that snakes spent on average 140 days in a burrow over winter, and that most males had entered hibernation by the beginning of May (autumn) while females did not begin till mid-May; the males mostly became active in the first week of September (spring), while the females not until the end of the month. The concrete slabs of houses have been used by eastern brown snakes hibernating in winter, with 13 recorded coiled up together under a slab of a demolished house between Mount Druitt

Mount Druitt is a suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a large ...

and Rooty Hill

Rooty Hill is a heritage-listed historic site and now parkland at Eastern Road, Rooty Hill, City of Blacktown, New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1802 to 1828. It is also known as The Rooty Hill and Morreau Reserve. The property is ...

in western Sydney, and another 17 (in groups of one to four) under smaller slabs within in late autumn 1972. Groups of up to six hibernating eastern brown snakes have been recorded from under other slabs in the area. In July 1991 in Melton, six eastern brown snakes were uncovered in a nest in long grass.

Eastern brown snakes are very fast-moving; Australian naturalist David Fleay

David Howells Fleay (; 6 January 1907 – 7 August 1993) was an Australian scientist and biologist who pioneered the captive breeding of endangered species, and was the first person to breed the platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus'') i ...

reported that the snake could outpace a person running at full speed. Many people mistake defensive displays for aggression. When confronted, the eastern brown snake reacts with one of two neck displays. During a partial display, the snake raises the front part of its body horizontally just off the ground, flattening its neck and sometimes opening its mouth. In a full display, the snake rises up vertically high off the ground, coiling its neck into an S shape, and opening its mouth. The snake is able to strike more accurately from a full display and more likely to deliver an envenomed bite. Due to the snake's height off the ground in full display, the resulting bites are often on the victim's upper thigh.

A field study in farmland around Leeton that monitored 455 encounters between eastern brown snakes and people found that the snake withdrew around half the time and tried to hide for almost all remaining encounters. In only 12 encounters did the snake advance. They noted that snakes were more likely to notice dark clothing and move away early, reducing the chance of a close encounter. Close encounters were more likely if a person were walking slowly, but a snake was less likely to be aggressive in this situation. Encountering male snakes on windy days with cloud cover heightened risk, as the snake was less likely to see persons until they were close, hence more likely to be startled. Similarly, walking in undisturbed areas on cool days in September and October (early spring) risked running into courting male snakes that would not notice people until close, as they were preoccupied with mating.

Reproduction

Eastern brown snakes generally mate from early October onwards—during the Southern Hemisphere spring; they areoviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and ...

. Males engage in ritual combat with other males for access to females. The appearance of two males wrestling has been likened to a plaited rope. The most dominant male mates with females in the area. The females produce a clutch of 10 to 35 eggs, with the eggs typically weighing each. The eggs are laid in a sheltered spot, such as a burrow or hollow inside a tree stump or rotting log. Multiple females may even use the same location, such as a rabbit warren. Ambient temperature influences the rate at which eggs develop; eggs incubated at hatch after 95 days, while those at hatch after 36 days. Eastern brown snakes can reach sexual maturity by 31 months of age, and have been reported to live up to 15 years in captivity.

Feeding

The eastern brown snake appears to hunt by sight more than other snakes, and a foraging snake raises its head like a periscope every so often to survey the landscape for prey. It generally finds its prey in their refuges rather than chasing them while they flee. The adult is generally diurnal, while juveniles sometimes hunt at night. The eastern brown snake rarely eats during winter, and females rarely eat while pregnant with eggs. The eastern brown snake has been observed coiling around and constricting prey to immobilise and subdue it, adopting a strategy of envenomating and grappling their prey. Herpetologists Richard Shine and Terry Schwaner proposed that it might be resorting to constriction when attackingskink

Skinks are lizards belonging to the family Scincidae, a family in the infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one of the most diverse families of lizards. Ski ...

s, as it might facilitate piercing the skink's thick scales with its small fangs.

The eastern brown snake's diet is made up almost wholly of vertebrates, with mammals predominating—particularly the introduced house mouse. Mammals as large as feral rabbits have been eaten. Small bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s, eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

, and even other snakes are also consumed. Snakes in areas of natural vegetation or paddocks for stock eat a higher proportion of reptiles, while those in crop fields eat more mice. Small lizards such as skinks are more commonly eaten than frogs, as eastern brown snakes generally forage in areas over distant from water. As snakes grow, they eat proportionately more warm-blooded prey than smaller snakes, which eat more ectothermic

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life ...

animals. Other snakes, such as the common death adder

The common death adder (''Acanthophis antarcticus'') is a species of death adder native to Australia. It is one of the most venomous land snakes in Australia and globally. While it remains widespread (unlike related species), it is facing increa ...

(''Acanthophis antarcticus''), and carpet python

''Morelia spilota'', commonly referred to as the carpet python, is a large snake of the family Pythonidae found in Australia, New Guinea ( Indonesia and Papua New Guinea), Bismarck Archipelago, and the northern Solomon Islands. Many subspec ...

(''Morelia spilota''), have also been eaten. Cannibalism has also been recorded in young snakes. The bearded dragon

''Pogona'' is a genus of reptiles containing six lizard species which are often known by the common name bearded dragons. The name "bearded dragon" refers to the underside of the throat (or "beard") of the lizard, which can turn black and gain we ...

is possibly resistant to the effects of the venom. Although the eastern brown snake is susceptible to cane toad

The cane toad (''Rhinella marina''), also known as the giant neotropical toad or marine toad, is a large, terrestrial true toad native to South and mainland Central America, but which has been introduced to various islands throughout Oceania ...

toxins, young individuals avoid eating them, which suggests they have learned to avoid them. Some evidence indicates they are immune to their own venom and that of the mulga snake (''Pseudechis australis''), a potential predator.

Venom

The eastern brown snake is considered the second-most venomous terrestrial snake in the world, behind only the inland taipan (''Oxyuranus microlepidotus'') of central east Australia. Responsible for more deaths from snakebite in Australia than any other species, it is the most commonly encountered dangerous snake in Adelaide, and is also found in Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney, and Brisbane. As a genus, brown snakes were responsible for 41% of identified snakebite victims in Australia between 2005 and 2015, and for 15 of the 19 deaths during this period. Within the genus, the eastern brown snake is the species most commonly implicated. It is classified as a snake of medical importance by theWorld Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

.

Clinically, the venom of the eastern brown snake causes venom-induced consumption coagulopathy; a third of cases develop serious systemic envenoming including

Clinically, the venom of the eastern brown snake causes venom-induced consumption coagulopathy; a third of cases develop serious systemic envenoming including hypotension

Hypotension is low blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood. Blood pressure is indicated by two numbers, the systolic blood pressure (the top number) and the dias ...

and collapse, thrombotic microangiopathy

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a pathology that results in thrombosis in capillaries and arterioles, due to an endothelial injury.

It may be seen in association with thrombocytopenia, anemia, purpura and kidney failure.

The classic TMAs are ...

, severe haemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vagi ...

, and cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. It is a medical emergency that, without immediate medical intervention, will result in sudden cardiac death within minutes. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and possib ...

. Other common systemic symptoms include nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis

Perspiration, also known as sweating, is the production of fluids secreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distribu ...

(sweating), and abdominal pain. Acute kidney injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously called acute renal failure (ARF), is a sudden decrease in kidney function that develops within 7 days, as shown by an increase in serum creatinine or a decrease in urine output, or both.

Causes of AKI are cla ...

and seizures

An epileptic seizure, informally known as a seizure, is a period of symptoms due to abnormally excessive or neural oscillation, synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Outward effects vary from uncontrolled shaking movements involving much o ...

can also occur. Onset of symptoms can be rapid, with a headache developing in 15 minutes and clotting abnormalities within 30 minutes; collapse has been recorded as occurring as little as two minutes after being bitten. Death is due to cardiovascular causes such as cardiac arrest or intracranial haemorrhage

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), also known as intracranial bleed, is bleeding within the skull. Subtypes are intracerebral bleeds (intraventricular bleeds and intraparenchymal bleeds), subarachnoid bleeds, epidural bleeds, and subdural bleeds ...

. Often, little local reaction occurs at the site of the bite. The classical appearance is of two fangmarks around 1 cm apart. Neurotoxicity

Neurotoxicity is a form of toxicity in which a biological, chemical, or physical agent produces an adverse effect on the structure or function of the central and/or peripheral nervous system. It occurs when exposure to a substance – specificall ...

is rare and generally mild, and myotoxicity (rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis (also called rhabdo) is a condition in which damaged skeletal muscle breaks down rapidly. Symptoms may include muscle pains, weakness, vomiting, and confusion. There may be tea-colored urine or an irregular heartbeat. Some of th ...

) has not been reported.

The eastern brown snake yields an average of under 5 mg of venom per milking, less than other dangerous Australian snakes. The volume of venom produced is largely dependent on the size of the snake, with larger snakes producing more venom; Queensland eastern brown snakes produced over triple the average amount of venom (11 mg vs 3 mg) than those from South Australia. Worrell reported a milking of 41.4 mg from a relatively large 2.1-m (6.9-ft) specimen. The venom has a murine

The Old World rats and mice, part of the subfamily Murinae in the family Muridae, comprise at least 519 species. Members of this subfamily are called murines. In terms of species richness, this subfamily is larger than all mammal families ex ...

median lethal dose

In toxicology, the median lethal dose, LD50 (abbreviation for "lethal dose, 50%"), LC50 (lethal concentration, 50%) or LCt50 is a toxic unit that measures the lethal dose of a toxin, radiation, or pathogen. The value of LD50 for a substance is the ...

() has been measured at 41 μg/kg—when using 0.1% bovine serum albumin in saline rather than saline alone—to 53 μg/kg when administered subcutaneously. While the lethal dose for humans is just 3 mg. The composition of venom of captive snakes did not differ from that of wild snakes.

The eastern brown snake's venom contains coagulation factors VF5a and VF10, which together form the prothrombinase The prothrombinase complex consists of the serine protease, Factor Xa, and the protein cofactor, Factor Va. The complex assembles on negatively charged phospholipid membranes in the presence of calcium ions. The prothrombinase complex catalyzes the ...

complex pseutarin-C. This cleaves prothrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma- ...

at two sites, converting it to thrombin

Thrombin (, ''fibrinogenase'', ''thrombase'', ''thrombofort'', ''topical'', ''thrombin-C'', ''tropostasin'', ''activated blood-coagulation factor II'', ''blood-coagulation factor IIa'', ''factor IIa'', ''E thrombin'', ''beta-thrombin'', ''gamma- ...

. Pseutarin-C is a procoagulant in the laboratory, but ultimately an anticoagulant in snakebite victims, as the prothrombin is used up and coagulopathy and spontaneous bleeding set in. Another agent, textilinin, is a Kunitz-like serine protease inhibitor that selectively and reversibly inhibits plasmin

Plasmin is an important enzyme () present in blood that degrades many blood plasma proteins, including fibrin clots. The degradation of fibrin is termed fibrinolysis. In humans, the plasmin protein (in the zymogen form of plasminogen) is encode ...

. A 2006 study comparing the venom components of eastern brown snakes from Queensland with those from South Australia found that the former had a stronger procoagulant effect and greater antiplasmin activity of textilinin.

The venom also contains pre- and postsynaptic neurotoxins; textilotoxin is a presynaptic neurotoxin, at one stage considered the most potent recovered from any land snake. Making up 3% of the crude venom by weight, it is composed of six subunits. Existing in two forms, the venom weighs 83,770 ± 22 daltons (TxI) and about 87,000 daltons (TxII), respectively. Textilotoxin is a type of phospholipase A2

The enzyme phospholipase A2 (EC 3.1.1.4, PLA2, systematic name phosphatidylcholine 2-acylhydrolase) catalyse the cleavage of fatty acids in position 2 of phospholipids, hydrolyzing the bond between the second fatty acid “tail” and the glyce ...

, a group of enzymes with diverse effects that are commonly found in snake venoms. At least two further phospholipase A2 enzymes have been found in eastern brown snake venom. Two postsynaptic neurotoxins have been labelled pseudonajatoxin a and pseudonajatoxin b. These are three-finger toxin

Three-finger toxins (abbreviated 3FTx) are a protein superfamily of small toxin proteins found in the venom of snakes. Three-finger toxins are in turn members of a larger superfamily of three-finger protein domains which includes non-toxic prote ...

s, a superfamily of proteins found in the venom of many elapid snakes and responsible for neurotoxic effects. Another three-finger toxin was identified in eastern brown snake venom in 2015. Professor Bart Currie coined the term ‘brown snake paradox' in 2000 to query why neurotoxic effects were rare or mild despite the presence of textilotoxin in eastern brown snake venom. This is thought to be due to the low concentration of the toxin in the venom, which is injected in only small amounts compared with other snake species.

Analysis of venom in 2016 found—unlike most other snake species—that the venom of juvenile eastern brown snakes differed from that of adults; prothrombinases (found in adults) were absent and the venom did not affect clotting times. Snakes found with a similar profile generally preyed upon dormant animals such as skinks.

The eastern brown snake is the second-most commonly reported species responsible for envenoming of dogs in New South Wales. Dogs and cats are much more likely than people to have neurotoxic symptoms such as weakness or paralysis. One dog bitten suffered a massive haemorrhage of the respiratory tract requiring euthanasia. The venom is uniformly toxic to warm-blooded vertebrates, yet reptile species differ markedly in their susceptibility.

Treatment

Standard first-aid treatment for any suspected bite from a venomous snake is for a pressure bandage to be applied to the bite site. The victims should move as little as possible, and to be conveyed to a hospital or clinic, where they should be monitored for at least 24 hours. Tetanus toxoid is given, though the mainstay of treatment is the administration of the appropriateantivenom

Antivenom, also known as antivenin, venom antiserum, and antivenom immunoglobulin, is a specific treatment for envenomation. It is composed of antibodies and used to treat certain venomous bites and stings. Antivenoms are recommended only if th ...

. Brown snake antivenom has been available since 1956. Before this, tiger snake antivenom was used, though it was of negligible benefit in brown snake envenoming. The antivenom had been difficult to research and manufacture as the species was hard to catch, and the amount of venom it produced was generally insufficient for horse immunisation, though these challenges were eventually overcome. Dogs and cats can be treated with a caprylic acid

Caprylic acid (), also known under the systematic name octanoic acid or C8 Acid, is a saturated fatty acid, medium-chain fatty acid (MCFA). It has the structural formula , and is a colorless oily liquid that is minimally soluble in water with a s ...

-fractionated, bivalent, whole IgG

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ...

, equine antivenom.

Captivity

Eastern brown snakes are readily available in Australia via breeding in captivity. They are regarded as challenging to keep, and due to the snakes' speed and toxicity, suitable for only experienced snake keepers.Notes

References

Cited texts

* * *Further reading

* Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry (2013). ''A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia, Fourth Edition''. Sydney: New Holland Publishers. 522 pp. .External links

Video: Eastern or Common Brown Snake

{{featured article Pseudonaja Reptiles of Papua New Guinea Reptiles of Western Australia Reptiles of Western New Guinea Reptiles described in 1854 Taxa named by André Marie Constant Duméril Taxa named by Gabriel Bibron Taxa named by Auguste Duméril Snakes of Australia Reptiles of New South Wales Reptiles of Queensland Snakes of New Guinea Reptiles of Victoria (Australia)